As breast cancer treatment comes to an end, it’s natural to expect a sense of relief and triumph. However, it’s common to experience a range of unexpected emotions, including feelings of abandonment, disappointment, and even a sense of anti-climax. The sense of abandonment can arise from the sudden withdrawal of the support network that has been present throughout treatment. The familiarity and routine of appointments and hospital visits may be gone, leaving many feeling lost and alone. This can be compounded by the ongoing fear of cancer recurrence, which can overshadow the sense of accomplishment. Another common emotion is disappointment at the lack of immediate joy or happiness following treatment. This can be attributed to the lingering side effects of treatment, the ongoing uncertainty about the future, and the sheer exhaustion from the physical and emotional demands of treatment. It’s important to remember that recovery takes time, and it’s okay to not feel elated immediately after your treatment ends. It’s not unusual to also feel fear or reluctance to celebrate your success, fearing that doing so might jinx any progress or tempt the cancer to return. This stems from our natural fear of the unknown and the desire to maintain a sense of control over the situation. This article – the fourth of Dr Jane Clark’s series on navigating life after cancer – focuses on taking stock emotionally after treatment and provides guidance on how to navigate this post-treatment period with resilience and optimism. Read on for Dr Clark’s insight and advice.

Taking stock emotionally

This article is adapted by Dr Jane Clark from an article originally written by Jane and Dr Peter Harvey. See our introduction for a background on this series of articles.

Many people describe the process being diagnosed and treated for cancer as being similar to being on an emotional rollercoaster. While you are on this rollercoaster, you are strapped in and sent off into an unknown world that is not of your choosing. You have to go where the rollercoaster takes you and you know that there is nothing that you can do about it until you emerge, wobbly and battered at the other end. It is only afterwards, when you are back on solid ground again, that you can look back and view what you have experienced and start to make sense of everything.

That is why many people need to take stock emotionally once the rollercoaster of treatment has stopped (or paused).

So, alongside your physical recovery, it is important to allow yourself some space to think and talk about the emotional experience of cancer and its treatment.

WHY DON’T I FEEL HAPPIER?

There are two sets of feelings that commonly arise at the time of treatment finishing which need to be talked about.

The first of these is a sense of abandonment. This makes sense. After all, for many weeks – if not months – you will have been cared for by a large number of people, all of whom have your welfare and well-being at heart.

You may have met other patients and relatives with whom you have been able to swap stories and get powerful support from someone who really understands. There has always been someone there to check out that little niggling pain or troublesome symptom. There has been a routine, a structure for you to trust in. Then all of a sudden, it goes.

“I got the impression of being balanced on a plank somewhere high up and with nothing to grab hold of. I felt as if I were about to fall off into some abyss.”

Such feelings of aloneness and abandonment are not in any way a criticism of the people who have been caring for you. It is simply a reflection of the fact that they now have to focus on those who are starting out on the process that you have completed.

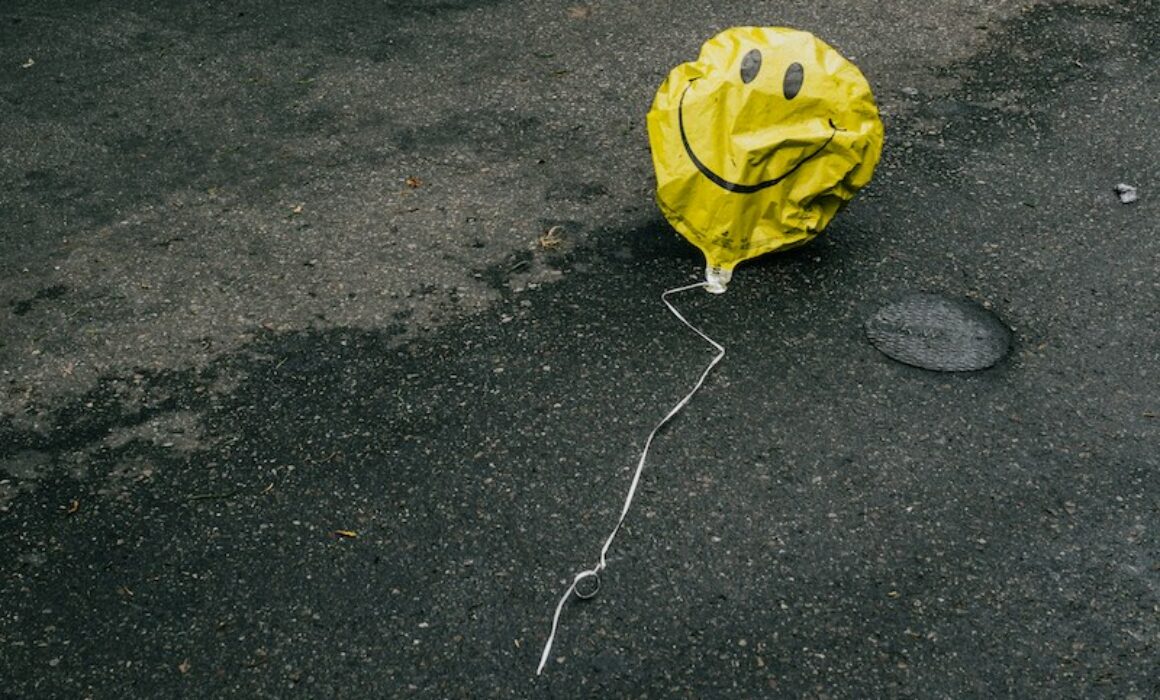

The second set of feelings that some people experience is a sense of disappointment that they don’t feel more joy and happiness at the end of treatment, but rather a sense of let-down, anti-climax almost. This can be in marked contrast to what they might have expected. How it is that hoped-for happiness does not arise?

There are a number of plausible explanations. One of these is that it hasn’t actually finished as you may still be experiencing the effects of treatment even though its delivery is complete. You may also be still visiting clinic for check-ups, so you are never really free of reminders of what you have been though. And there is the uncertainty and sense of threat that may continue well beyond the actual end of treatment (see Life After Breast Cancer: How to live with uncertainty and manage the fear of recurrence).

There is also the fact that you may be completely de-energised – plain exhausted – which does not leave much spare capacity for unrestrained ecstasy (see Life After Breast Cancer: How to deal with fatigue.)

In addition, you will have been looking forward to the absence of something unpleasant rather than the eager anticipation of the arrival of something pleasant. In other words, the end of treatment is the end of, very probably, a negative and unpleasant time and whilst this may bring a sense of relief, it does not mean the arrival of something positive so may not bring a sense of joy and happiness. (So perhaps it’s not such a surprise that that there is lack of elation as treatment finishes.)

KEEPING THINGS ON A LEVEL

Some people worry about celebrating the end of treatment for fear that this celebration will somehow tempt the cancer to return.

“If I truly believe that it’s gone then it will bite me in the bum by coming back”

It’s almost as if it’s too risky to celebrate the success of finishing treatment.

“If I get too high celebrating the possibility that the cancer has gone then it will be too hard a fall if/when it comes back again”

Sometimes it is tempting to keep your emotions on a level as it feels safe. It makes me think of the ‘Heart and the Bottle’ children’s book (by Oliver Jeffers, which I highly recommend). It tells the story of a curious and inquisitive child who suffers a bereavement. She decides to put her heart in a safe place – in a bottle around her neck. She thinks this solution fixes things but, over time, she realises what she is missing out on. I would encourage you to think about what you lose by trying to stay on a level in a bid to protect yourself from the potential falls. We are vulnerable when we live, love and experience the highs and lows of life but can you tolerate that vulnerability (and the possible lows) in order to feel the full joy and possibility of life?

Only you can make that decision but consider the possibility that you can define your life and your emotions rather than the cancer.

Dr Jane Clark, Consultant Clinical Psychologist

FURTHER INFORMATION

The next article in this series of articles focuses on some of the unhelpful things that people might say to you after cancer, and how to deal with them. You can read it here 5: Life After Breast Cancer: unhelpful things you shouldn’t say to cancer patients.

If you’re looking for more support, Future Dreams hold a range of support groups, classes, workshops and events to help you and your carers during your breast cancer diagnosis. These are held both online and in person at the London-based Future Dreams House. To see what’s on offer and to book your place, see here.

To return to the homepage of our Information Hub, click here where you can access more helpful information, practical advice, personal stories and more.

This page was reviewed in April 2024 by the Future Dreams team.

The information and content provided in all guest articles is intended for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to substitute for professional medical advice. It is important that all personalised care decisions should be made by your medical team. Please contact your medical team for advice on anything covered in this article and/or in relation to your personal situation. Please note that unless otherwise stated, Future Dreams has no affiliation to the guest author of this article and he/she/they have not been paid to write this article. There may be alternative options/products/information available which we encourage you to research when making decisions about treatment and support. The content of this article was created by Dr Jane Clark, Consultant Clinical Psychologist and we accept no responsibility for the accuracy or otherwise of the contents of this article.

©️ 2023 Jane Clark and Peter Harvey. With quotes from the creators of the Ticking off Breast Cancer website (now Future Dreams Information Hub). All rights reserved.

Share

Support awareness research

Donate to those touched by BREAST cancer

Sylvie and Danielle began Future Dreams with just £100 in 2008. They believed nobody should face breast cancer alone. Their legacy lives on in Future Dreams House. We couldn’t continue to fund support services for those touched by breast cancer, raise awareness of breast cancer and promote early diagnosis and advance research into secondary breast cancer without your help. Please consider partnering with us or making a donation.